Cities, Inequality, and Wages

Economic inequality has been mounting in the United States, hitting levels not seen since the Gilded Age. There are numerous explanations for this phenomenon, ranging from the decline of unions and high-paid manufacturing jobs to the rise of globalization, of new technology, and knowledge-based work (what economists call "skill-based technical change") and the bifurcation of the labor market into high-skill and low-skill jobs.

But do our cities and changing economic landscape play a role as well? There are good reasons to suspect that they do. For one, the past decade or so has seen a sorting of population by skill, occupation and human capital, (see my 2006 article "Where the Brains Are"). For another, it is well known that both highly skilled and talented people and productive firms and high-tech industries tend to cluster and agglomerate together to create powerful economic advantages.

An important study entitled "Inequality and City Size" by Ronni Pavan of the University of Rochester and Nathaniel Baum-Snow of Brown University and the National Bureau of Economic Research takes a close look at this issue. Using data from the American Community Surveys of the U.S. Census, Pavan and Baum-Snow tracked the gap between the lowest and highest reported incomes across U.S. between 1979 and 2004, from the smallest rural areas to the biggest urban centers. They examine the effects of city size on wages while controlling for factors like human capital and work effort -- key factors in determining wages outlined in the seminal work of labor economist Jacob Mincer -- and the composition of local industry.

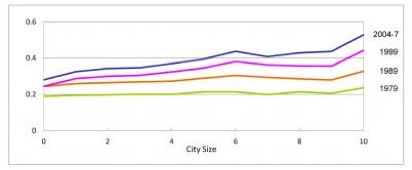

The chart below, adapted from their study, shows their key findings. The X axis is based on city or metro size -- ranging from rural areas indicated by a 0 to the largest metropolitan regions. The Y axis shows the level of inequality. The green line is for 1979, orange for 1989, magenta for 1999, and blue for 2004-07.

In 1979, the line was relatively flat, rising only slightly for the largest metros: Inequality was relatively the same regardless of whether you lived in a rural community, small city, or large metro. But with each passing decade the slope grows steeper, the gap between haves and have-nots growing progressively larger by city size. The study finds that city-size alone accounts for roughly 25 to 35 percent of the total increase economic inequality over this period over and above the role of effects of skills, human capital, industry composition and other factors. This effect is more pronounced among lower wage earners. City size explains 50 percent more of the increase in inequality for the lower half of the wage distribution than for the upper half, the study finds.

"Something fundamental has changed in our economy, and it's happening at the metropolitan level," explains Baum-Snow. "If we want to understand what's causing the wage gap, we now know we need to look at the unique economies of our larger cities," adds Pavan.

Both the U.S. and the world have grown increasingly spiky, with our socio-economic divide increasingly overlaid with a growing economic geography of class. Big cities like New York and LA have attracted wealthy people not just from America but from around the world. This trend reflects the growing advantages of geographic clustering or agglomeration. The larger and more populous a city or region, the more likely it is to have the human capital and economic ecosystems required to support the most advanced -- and hence the highest-paying -- technologies and industries. Bigger cities attract more innovators, more entrepreneurs, and more highly skilled and ambitious people in general, and provide a fluid environment where these individuals can combine and recombine their skills. Big cities also generate powerful economies of scale and scope, resulting in higher rates of innovation, new firm formation, and productivity. They attract better-educated, better-trained, more-experienced workers, driving up wages.

At other side of the spectrum, manufacturing, which once clustered in and around large cities and metros, has shifted to less expensive suburban, exurban, and off-shore locations. And large cities have become home to a large and growing contingent of lower-skill, lower pay service jobs -- from childcare and food preparation to retail sales and personal services. Taken together these factors have in effect divided or bifurcated the labor market in big cities into highly paid "creators" and much lower-paid "servers."

Despite this divide, big cities may still offer a better environment for less-advantaged, lower-skilled workers. As urban thinkers from Jane Jacobs to Edward Glaeser have argued, big cities improve economic conditions for everyone, including the least well-off, compared to what they could expect in smaller cities or in the countryside. Big cities typically offer better paychecks even for low-skill jobs. And even though housing and other costs are higher, bigger cities provide more opportunities and a thicker labor market for just about anyone to move up the socio-economic ladder and find new opportunities when needed.

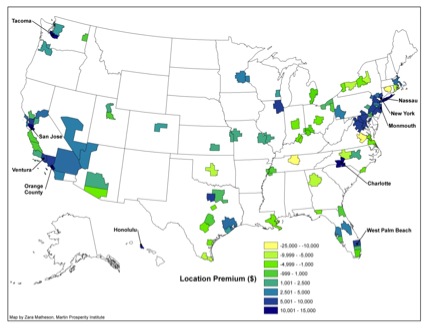

With the help of my colleague, Charlotta Mellander, I took a quick look at the association between cities and wages. Using micro data on millions of individuals across U.S. metros, Mellander calculated the residual values for the average wage across these metros. This amounts to a location premium which shows how much, on average, the metros pay in wages after controlling for skills, education and hours worked.

Workers on average gain the most from living and working in San Jose, California, where the location premium is $13,479. The location premium is above $10,000 in the metros -- Charlotte, Orange County, and Nassau. New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, the District of Columbia, Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Francisco, Minneapolis, and Houston number among the top 20 metros on this measure (see the map above).

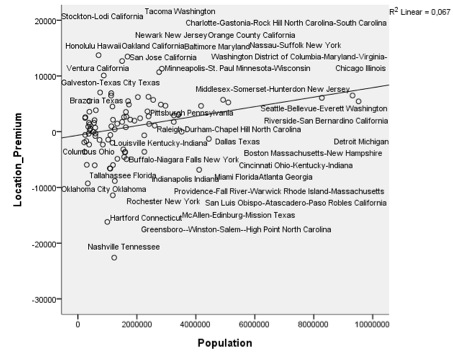

Mellander then ran a basic correlation analysis comparing this location premium to city size. Not surprisingly, the correlation is positive and significant (with a coefficient of. 24). While not overwhelming, it suggests a modest association between average wages and city size (see the scatter-graph below). Bigger cities or metros on average pay higher wages overall, even when skills, education and work effort are taken into account.

All of this leads to an intriguing conclusion about the connection between cities and wages. On the one hand, city-size has become a factor in increasing inequality, magnifying the underlying bifurcation of the labor market. On the other hand, bigger cities appear to pay better average wages. Cities make us richer, more productive, and increase our wages, even as they reflect and compound the growing social and economic divides of today's increasingly spiky world.